China's interest in imported wheat and corn is rapidly declining, which is likely to put pressure on global grain markets accustomed to robust demand from the world's largest agricultural importer.

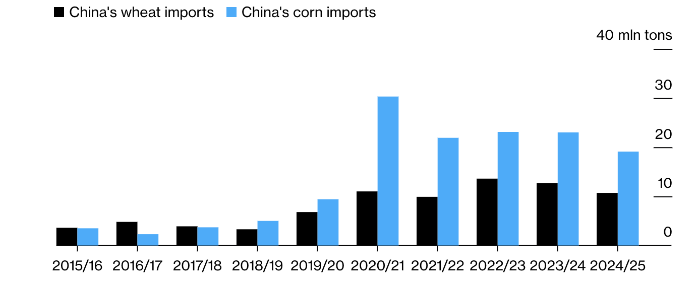

China only began importing wheat and corn during Trump's presidency. Source: Bloomberg

According to a number of traders, buyers in China have not made large purchases for several months. Given low domestic prices, this trend is likely to continue in the third quarter, they said on condition of anonymity.

The International Grains Council and the US Department of Agriculture continue to count on significant purchases from China this year and next. If imports fall sharply, a key component of demand will be at risk, inevitably hitting farmers from America to Europe to Australia.

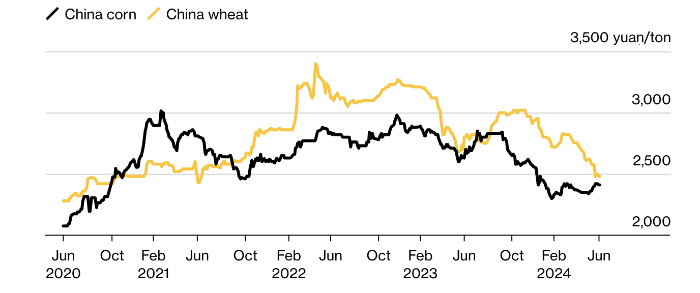

The fall in import demand is attributed to a sluggish economy and consecutive record harvests in China. The government was forced to stockpile wheat and corn to support local farmers, while external supplies were limited or even canceled to stabilize the domestic market.

This should alarm China's foreign suppliers, especially after Turkey, the world's fifth-largest wheat buyer, suspended grain imports for four months to protect local producers. Weak consumption from China, the second-largest importer, will only add to market nervousness.

"The economy is really bad, and overall demand from the whole society is falling," said Ma Wenfeng, a senior analyst at consultancy BOABC in Beijing. "The government wants to increase grain prices and increase farmers' incomes to boost demand in rural areas. It is better to buy grain domestically than from abroad."

China has been buying soybeans in large quantities for a long time. It mainly goes to feed pigs. But the explosive growth in demand for wheat and corn, which are also used in animal feed, came only as part of China's diplomatic commitments during the trade war with the Trump administration.

Imports of wheat and corn from January to April were actually faster than last year. This makes the sudden drop in activity even more striking and could leave international markets vulnerable to falling prices if China does indeed adjust its overseas purchasing strategy.

In the last full week of May, the U.S. had just 86,300 tons of corn left to ship to China in the current marketing year that ends in August, down sharply from 631,600 tons last year, according to USDA data. There are no outstanding corn sales for next seasonÑsomething that hasn't happened for five yearsÑand just 62,500 tons of wheat.

Grain price dynamics in China

Although the situation could change quickly, especially if bad weather affects harvests, China's grain surplus is unlikely to decline significantly while consumption remains so weak. In addition, experts are predicting another record year in terms of wheat and corn harvests.

Improving harvest conditions will likely help reduce China's wheat deficit from nearly 17 million tons this marketing year to less than 7.5 million tons in 2024-25, according to Charles Hart, senior commodities analyst at BMI, a unit of Fitch Solutions. years, which will lead to a decrease in import demand. He said corn imports would also decline in 2024-25 as production increases.

Demand for feed

On the demand side, China's pig population is declining and meat consumption remains subdued. Mysteel Global expects that half as much wheat will be used for animal feed from the new harvest as last year. Margins at mills that make flour for cakes and bread are also suffering as people cut costs, Mysteel reports.

This means less imports. China's Ministry of Agriculture forecasts that corn supplies in the new marketing year will fall by a third, to 13 million tons, from 19.5 million tons estimated for this year. The USDA still expects 23 million tons, although it may revise that figure on Wednesday when it releases monthly forecasts.

In fact, supplies may fall even further. China manages imports under a quota system that will allow just over 7 million tons of corn and nearly 10 million tons of wheat to be imported this year at the lowest tariff of 1%. After this, duties jump to 65%. While buyers will be eager to use up their quotas, the economics of importing beyond that make much less sense, said BOABC's Ma.

ÒAt the end of the day, we donÕt need so many imports, given the record harvests and, more importantly, the significant decline in consumption,Ó he said.

Please visit our Farming articles directory.